Introduction: When living in a country for the purpose of exploring it, exploration must be done. Sometimes, though, it’s good to have a guide. This week, we had Iris for a private tour, arranged at the last minute through Panama Road Trip Adventures (http://panamaroadtrips.com/).

The tour included a one-way train trip all the way across the country (all 50 miles!); a drive out to Fort San Lorenzo, a UNESCO World Heritage Sites and one of the oldest Spanish forts in the Americas; a tour of the Agua Clara Locks, one of the new sets completed in 2016 that take the huge Neo Panamax ships, and lots of insider information about Panama and its culture that will be woven in and out of this and other upcoming blogs.

Iris had spent two years as an au pair for triplets in Ohio. Her English was good, and her knowledge of the history and current society of Panama was terrific, and she was an excellent driver on some really bad roads.

Here’s what we did:

Train Trip!

The California gold rush of 1849 is what really put Panama on the U.S. map. Looking for easier ways to cross the continent than wagon trains from Missouri to California and a shorter way to get from east to west than to sail around the tip of South America, gold prospectors figured a 50-mile trip from the Caribbean to the Pacific across the isthmus of Panama would be a good way to go. In spite of a volcanic mountain chain in the way, American entrepreneurs saw an opportunity, and the U.S. government subsidized the railway’s construction starting in 1850. Trains began running in January 1855, and the railroad proved essential for the building of the Panama Canal some 65 years later.

As the U.S. began to pull out of the Canal Zone starting in the late 1970s, the railroad fell into disuse. However, the Panamanian government decided to revitalize the railroad—especially for transporting freight—starting again in 1998. The railroad was repaired, and a new era of nostalgia-imbued passenger service began. Mostly the train takes commuters from Panama City to Colon for work, but one car, with big glass observation windows, is devoted to tourists.

The railway office opens at 6:30, mas o menos, and the rush is on to get tickets for good seats because the passenger service goes from Panama City to Colon at 7:15 a.m. and returns at 5:15 p.m. Monday through Friday, and that’s it. Iris hurried us on board while she bought our tickets because she didn’t want us to miss the opportunity ride in the beautiful, wood trimmed observation car.

The views from the train—lakes, mountains, swamps, jungle, canal—are wonderful. We saw many egrets, ospreys, and other water birds along the way. And ships! We had several opportunities to see big ships because the railway mostly parallels the Panama Canal (http://heathers6wadventures.com/coolest-place-en-el-mundo/). We got an OK cup of coffee and some good carbohydrate-filled snacks from the cute train conductress.

Train view of rain

Train view of a ship on canal

Train view of Gatun Lake

Views from the train window

Train window looking at the canal

After an hour-long, smooth ride, we disembarked from the train at the station in Colon. Iris was there to meet us with her trusty Nissan Qashqai SUV (not a style sold in the U.S.).

Colon

Originally called Aspinwall after the founder of the Panama Railway, the town the world now calls Colon (Spanish for Columbus) was purposely built starting in 1850 to provide a terminus for the railroad and a port of entry on the Caribbean coast. Today, it is the northern (Caribbean) entrance to the Panama Canal, and has a large duty-free shopping area. In spite of these economic advantages, it is rusty and run down and has reputation as a seedy place. Tourists are warned not to visit without a guide.

Iris explained some of the history. Because the Caribbean coast of Panama is sparsely populated and riddled with inlets and islands, it has been used since the days of British pirates as a place from which to smuggle and raid. Colombian drug cartels, with the help of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, used it for the same thing in the 20th century. Thus, still today, Colon is reportedly full of gang members, robbers, and other bad hombres. We drove through without really exploring much. The road led us to

A Really Old Fort.

Readers of this blog from New Mexico will recognize this story. A UNESCO World Heritage Site at the end of a horrible road. Locals debate: do we keep the road bad to keep people away and help preserve the site or do we improve the road so more people can see and appreciate it? Fort San Lorenzo aficionados have the same debate as we lovers of Chaco Canyon. I say, let’s keep the roads bumpy!

And so, Iris drove around big potholes and ruts and even a little stream that cut across the road. Thankfully, we were the only ones on the road. We had to go past an armed guard, who boredly waved us on through the big gate.

As we drove along, with Iris telling us about the history of the area, suddenly, in the jungle above us, I spotted a howler monkey (mono aullador en Espanol). He stopped and posed for photos, which we thought was quite kind. We also saw many coatis (gatosolo en Espanol), the same long-tailed critters that frolicked during our visit to Parque Natural Metropolitano (http://heathers6wadventures.com/bosque-encantado-enchanted-forest/).

Finally, the road opens out of the jungle onto a cliff overlooking the mouth of the mighty Rio Chagres. This strategic location, until the railroad and canal came along, was the main route from the north to Panama City. Travelers followed the river for about 30 miles inland and then took old indigenous/Spanish trails/roads to the city. Spanish gold from its South American conquests traversed the route for years.

To protect this vital inlet/outlet for its trade, the Spanish crown commissioned Fort San Lorenzo in the late 1500s. Francis Drake was the first English privateer to attack. That old scallywag Henry Morgan took the place nearly a hundred years later before invading Panama City.

The fort has been rebuilt several times, the last time in the 1700s. UNESCO declared it a World Heritage Site because it, along with its twin fort Portobello on the other side of Colon, are “magnificent examples of 17th- and 18th-century military architecture.”

We had the place practically to ourselves. A small tour van was just leaving when we arrived, and a taxi carrying a tourist who had been on the train with us, braved the road. It was a beautiful and, considering it’s an old military fort, peaceful setting.

We saw the little boat that takes the Panama Canal pilots from the shore to the ships. I was a little jealous, but that was fun.

Sadly, there is a huge missed opportunity along the winding road out to the fort. The old U.S. Army barracks of Fort Sherman, which are right on the beach amid palms and mangroves, are crumbling. Someone could have opened them as a beach-front condos or a resort, hired private security, and made a lot of money. Instead, it’s a sad, lonely place, watched over by that bored guard.

However, just a few miles away is a bustling busy

New Set of Locks.

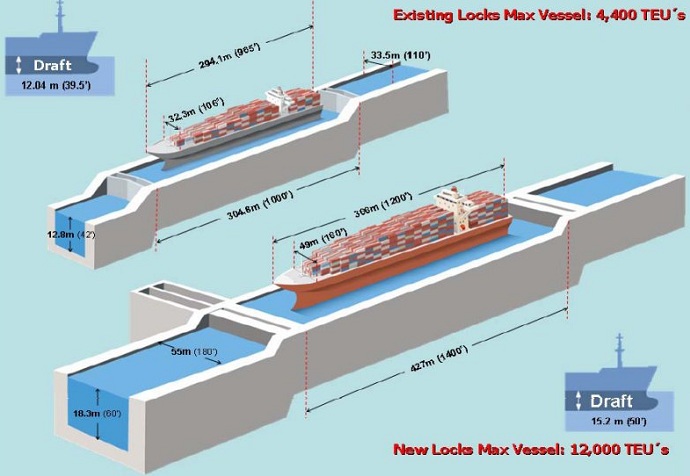

As mentioned in the blog on the Panama Canal, the canal was expanded in 2016, with new locks to accommodate the huge Neo Panamax ships. The new locks are 60 percent wider and 40 percent longer than the old ones. Ninety-eight percent of the ships in the world can go through the Panama Canal. (Ships that cannot are called Post Panamax.)

I love big ships

Big ship leaving the locks

Big ships

Ship being moved in

Lock gates open

Big ship!

Lock gates closing

We spent quite a bit of time at the new Agua Clara Locks visitors center, learning about the new lock gates, the water conservation retention ponds, and the really big ships. The new ships can carry up to 13,000 containers, compared to 5,000 for the regular ships. That’s 13,000 semi-trailers on one ship. Amazing!

We watched a big liquid petroleum gas ship, which we speculated had taken LPG from Houston to China and was empty and headed back to Houston, lower from Gutan Lake to the Caribbean. The ship, with the rather funny name of Wisdom Gas, didn’t do much. It was the little tugboats that pulled and pushed it into the locks that worked really hard. We could probably have stayed there all day watching, if our tour had allowed it.

About 10,000 people work for the Panama Canal, and 99.9 percent of them are Panamanian, making me super jealous. I’ve finally figured out in a future life I want to be a pilot on the Panama Canal. But for now, I’m too old and too American.

Oh, well. I guess that means we have more exploring to do.

So, we rode back across the isthmus in Iris’ SUV for about an hour, watching for birds, crossing lots of rivers (including Rio Agua Sucio—Dirty Water River!), hearing more stories about Panama and its history and getting our questions answered. Then we got stuck in traffic in Panama City. Enough said.