Giant tortoises. Huge colonies of squawking Blue-Footed Boobies. Beaches filled with sun-basking iguanas. These are probably what you’ve seen in nature shows and documentaries over the years about the Galapagos Islands. Those are all true and some of what you will see when you visit.

If you’ve read any of Charles Darwin’s accounts (Voyage of the Beagle is actually an interesting read, although he’s kind of mean to the iguanas), you’ll expect bleak landscapes with rough volcanic beaches, scrubby leafless trees, and strange animals, unlike any others on the planet. Those are also all true and some of what you will see when you visit.

What you won’t see on TV and probably don’t know about are bustling towns, fantastic restaurants, farms and ranches, mass transportation on land and sea, and a community that takes care of its own.

A bit of history

As far as archaeologists and those who study such things can tell, no ancient cultures lived on the Galapagos. That makes sense because fresh water is non-existent on some of the islands and scarce on others. Pirates, whalers, and erstwhile wayward sailors began stopping off in the islands in the 1500s, and by the time Darwin arrived in 1835, a small colony of mostly former Spanish convicts lived in the highlands of San Cristobal (then Chatham) Island. While the sailors and others ate giant tortoises and killed them for their oil, they didn’t exploit the islands that much. What they did do was leave behind goats, pigs, cattle, horses, and rats who ravaged the endemic and native species.

With the assistance of international scientific groups and agencies, the Ecuadorian government established the Galapagos as a national reserve in 1936 and converted all of the islands, except for land already owned by settlers, into a national park in 1959. Ninety-five percent of the island lands and the surrounding ocean are now a park and marine preserve. Tourism, which changed from a trickle in the 1930s to a flow in the 1970s to a gush today, remains tightly controlled, with intense regulation of tour operators. Tourists are allowed only in designated areas, and, outside of the towns, only under the supervision of licensed guides.

When Adriano Cabrera moved from mainland Ecuador to Santa Cruz Island in the Galapagos more than 130 years after Darwin’s visit, he acquired a patch of land in the highlands for sugarcane, chocolate, and coffee farming, trades he continues today. In the early days, he says, one boat a year landed on the island. Over time, one boat a month arrived, and now, hundreds of tourists arrive daily.

Transportation

In fact, some 150,000 tourists visit the islands annually. Before embarking on a flight, visitors must get a $20 Transit Control Card. Flights from Quito usually stop off at the coastal city of Guayaquil and then quickly hop over 500 miles of Pacific. The U.S. built the main Galapagos airport in the 1940s to protect the Panamá Canal on the tiny, uninhabited island of Baltra. It was turned over to the country of Ecuador after World War II. Rebuilt in the 2000s, the airport prides itself on being carbon neutral, the world’s first “ecological airport.”

From the airport, visitors take a bus to the ferry. A brief ride across the canal lands on Santa Cruz Island, where another bus transports them from a volcanic desert landscape up over the lush highlands full of meandering Giant Tortoises and down to the bustling port of Puerto Ayora.

In the port, water taxis ($1, cash only) hustle from dockside to larger boats, either for tours or ferries to other islands. The port bustles with its ferries, tour boats, fisherman, busy ocean birds like Brown Pelicans and Magnificent Frigate Birds, and kids swimming near the boat ramp. Over all of it, sea lions who do, in fact, own the place, bark loudly at each other.

The Wildlife

The real purpose for visiting the Galapagos, following in the footsteps of Darwin and other naturalists, is to see the animals and birds. The animals have little to no fear of humans. The sea lions take over benches, rafts, or any other flat surface that sparks their sleepy fancy. They climb onto docks, block boats, and thrill snorkelers and divers by coming along side to swim for a while. In one instance, a young sea lion stopped in front of me on the sidewalk and turned its head back and forth, obviously posing for photographs. It still makes me laugh!

The birds were numerous and fun. When I was a small child, either Sesame Street or Captain Kangaroo had a piece on Blue-Footed Boobies. The tune was catchy, the turquoise feet fascinated me, so I’ve wanted to see them since then. I finally got to! They are big, and beautiful, and they met all my expectations. From the soaring Magnificent Frigate Birds to scampering Darwin’s Finches and the flashy Yellow Warblers, we saw a good number of interesting birds, some of which differed from their mainland counterparts (mockingbirds, finches) and helped make the islands famous.

A two-hour ferry ride from Santa Cruz to Isabela took us to the lovely town of Puerto Villamil, with its white-washed building and blue satellite dishes. After riding a local taxi intended for 25 but stuffed with 40 (we love authentic experiences) we visited a tortoise breeding center (biologists have to keep rescuing them from active volcanic areas), and we got to see flamingos, which are native to the island. Our main purpose for that portion of the trip was to see the famed Galapagos Penguin, the smallest in South America, and the only one that lives close to the equator. We saw one – yes one! – Galapagos Penguin. The little guy was so photogenic that he was completely worth the trip.

The stars of the islands, though, are the tortoises. There are two types, the Galapagos Tortoises (galapagos is an ancient Spanish word for turtle), which reach up to eat leaves, and the Giant Tortoises, which eat grass and other ground cover. Each island has its own species and, on Isabela, sub-species exist in various volcanic areas, cut off from their cousins by, among other things, hot lava.

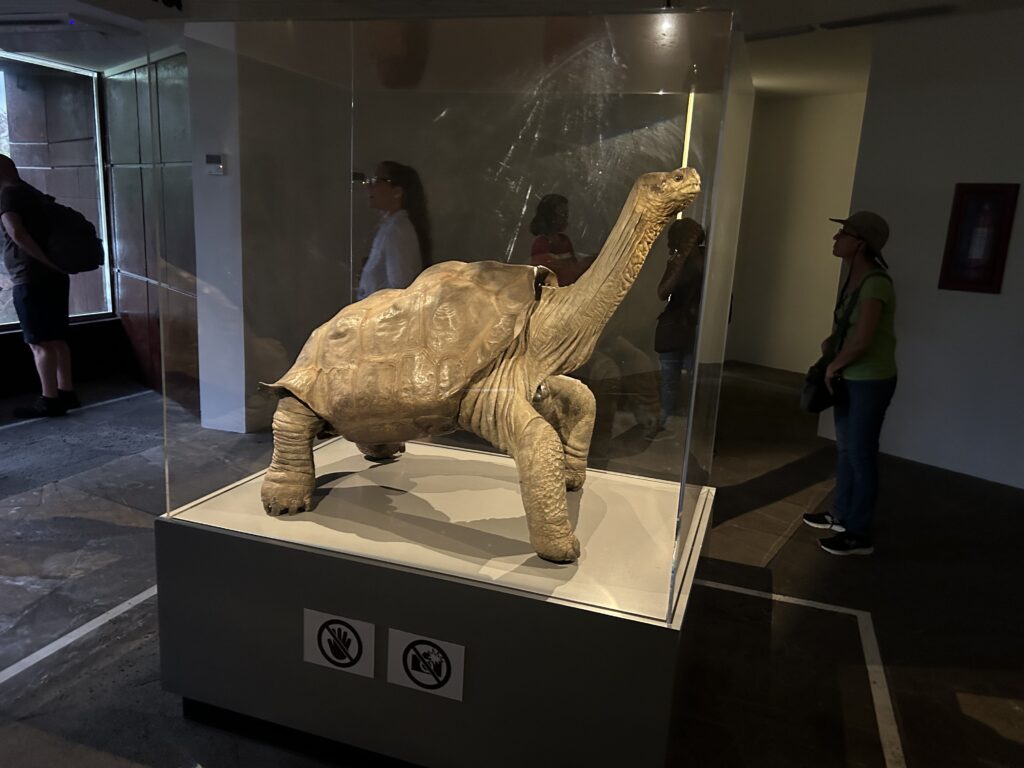

One of the highlights of our visit was the Charles Darwin Research Station (https://www.darwinfoundation.org/en/about/cdrs), which serves as a breeding center for the tortoises. They are released into the wild after five years at the center, when their shells are hardened, and their size is great enough to overcome predation. Also on display is Lonesome George, the taxidermized remains of the last tortoise from Isla Pinta, whose DNA wasn’t compatible with tortoises from any other islands, and who wasn’t interested in breeding, anyway.

As part of our tours, we snorkeled with sea turtles, white-tip sharks, dozens of beautiful fish species, urchins, and other sea creatures. Bob went scuba diving, coming within yards of hammerhead sharks, sea turtles, a scorpion fish, morae eels, sea lions, and some of the most vibrant fish he’s ever seen.

The Town

All of these tours, animal viewings, and boat trips would not have been possible without the port. Puerto Ayora is not particularly attractive. Like many Latin American towns, it’s a jumble of concrete block buildings, corrugated tin roofs, mini-markets, hole-in-the-wall restaurants, and winding streets. We had a nice hotel (https://hotelalbatross.com.ec/) , but our balcony faced a solar panel farm (good thing) and a busy, loud construction site (not so good).

The main street, Charles Darwin, reminded us of Kona, Hawai’i. With its high-end shops, trendy bars and restaurants, and souvenir stalls, it could have been any waterfront tourist town. A block away, however, on Charles Binford Street, the locals gathered for the best and freshest seafood. Here is where we had an amazing grilled lobster meal (and lots of sangria) for about $25 each. Here is where we learned how to make ceviche. Here is where Chef David saw us on our last night in town and gave us a farewell hug. It is a nightly riot of sounds, colors, delicious smells, mouthwatering foods, and fun. (Note: We googled Charles Binford every which way we could and found no information on him. Our guide said he was a naturalist like Darwin, just not as famous. We’ll have to go with that.)

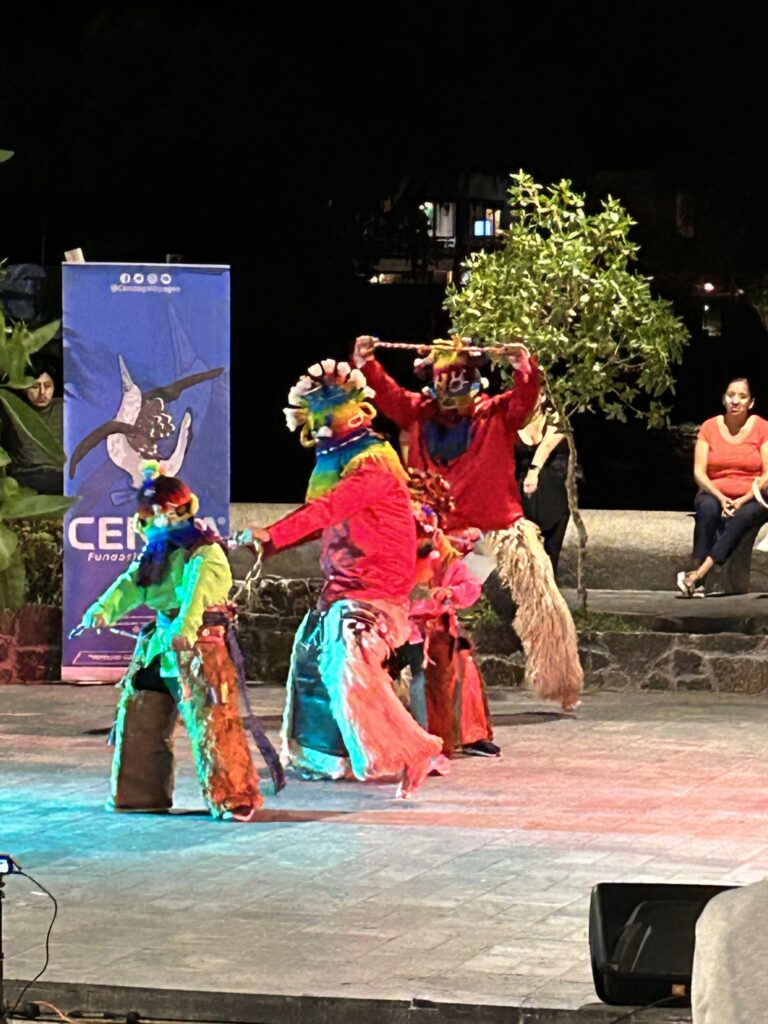

All of our guides on the islands were quick to point out how safe the town is and that there are no social problems like thievery, homelessness, rampant drug or alcohol abuse, etc. We saw some of this on Halloween, as parents with small children strolled throughout town, trick or treating at local businesses and visiting on the pier. Teens were out and about on their own, laughing, enjoying the beautiful evening, gathering candy where they could, and contributing to the comfortable vibe. Another night we caught a dance recital, right on the sea front.

So, put the Galapagos on your bucket list. Take the tours and buy the souvenirs because you really will contribute to preserving the wildlife of this unique environment. It’s definitely a place worth visiting.

One final note: Regular readers of this blog may remember our visit to Santa Fe, Panamá, several years ago (https://heathers6wadventures.com/the-city-of-holy-faith-santa-fe-not-new-mexico/) where I mentioned the roosters made noise not just at dawn but really any time they felt like crowing. The roosters in Puerto Ayora are the same. They usually started crowing around 3:20 a.m. and kept it up until the sun was well up. National Geographic probably won’t tell you about that, either.

Very well written and extremely interesting and informative!

Heather, You captured our visit to the Galapagos perfectly! It was an amazing trip and traveling with friends made it even more memorable and fun! 🙏🥰🙏

Thanks! It was fun to get back into the swing of blogging.

Excellent blog entry! I enjoy your travels and all the photos you post, however, this blog neo ga the visited place to the reader in great detail! Thank you for taking/making the time to do this!

Speaking for Butch and myself, we loved your vibrant article! I agree with Jonna that your captured our journey with such accuracy. It was truly a one of a kind experience with special friends. “Thanks for the memories!”

Thanks for the highlights!